BBC News

Reporting fromWindsor, Ontario

Ali Abbas Ahmadi/BBC

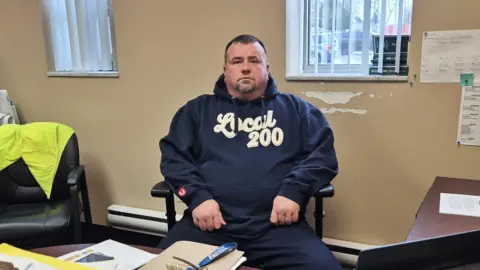

Ali Abbas Ahmadi/BBCA Lawton has worked in Canada’s auto sector for more than a century.

Their children are “fifth generation Ford workers”, Kathryn Lawton said, and she and her husband both work for the carmaker in Windsor, the heart of Canada’s automobile sector, just a bridge away from the US state of Michigan.

So when US President Donald Trump suggested that Canada stole the American auto industry, Chad Lawton calls it “ludicrous”.

“These were never American jobs. These were Canadian jobs,” he told the BBC, on the day that Trump’s auto tariffs came into force.

“They’ve always been Canadian jobs, and they’re going to stay Canadian jobs because we didn’t take them from them. We created them, we sustained them.”

Kathryn agreed: “This is Ford City right here.”

Tucked away in southwestern Ontario, Windsor and the surrounding Essex county now finds itself on one of the front lines of Trump’s trade war as it faces a 25% tariff on foreign-made vehicles (though for Canada, that will be reduced by half for cars made with 50% US-made components or more) as well as blanket 25% US tariffs on steel and aluminium imports.

US tariffs on auto parts are expected next month.

Ali Abbas Ahmadi/BBC

Ali Abbas Ahmadi/BBCThe region of just over 422,000 grew alongside Detroit – nicknamed Motor City for its role as an auto manufacturing hub – turning the region into an important centre for North American automobile production.

Ford first established its presence in Windsor in 1896, while the first Stellantis (then Chrysler) factory arrived in 1928, with dozens of factories and suppliers springing up around the city and surrounding region in the ensuing decades.

Much of the manufacturing has since left the city, though it still boasts two Ford engine factories and a Stellantis assembly plant, which employ thousands.

Workers on both sides of the border have built iconic vehicles over the decades, most recently models like the Dodge Charger and the Ford F-150.

Some 24,000 people work directly in the automotive industry in Windsor-Essex, while an estimated 120,000 other jobs depend on the sector.

A drive through the neighbourhood around the Ford factory feels like a trip back in time, showcasing classic bungalows from the last century. Many have seen better days, though each boasts a verandah and small front yard. Large murals celebrating the city’s automotive history punctuate the scenery.

Ali Abbas Ahmadi/BBC

Ali Abbas Ahmadi/BBCWindsor has weathered the challenges of the North American auto sector alongside Michigan, as the industry shares a deeply integrated supply chain.

Chad Lawton points to the 2008 financial crisis, when the Big Three American automakers – Ford, General Motors and Chrysler – faced staggering losses, and GM and Chrysler received billions in US bailouts to avoid bankruptcy.

That period was “bad, not just for next door, but also we went through a very, very rough time”, he said.

“This feels the same. The level of anxiety with the workers, the level of fear, the idea and the belief that this is just something that is so completely out of your control that you can’t wrap your head around what to do.”

John D’Agnolo, president of Unifor Local 200, which represents Ford workers in Windsor, said the situation “has created havoc”.

“I think we’re going to see a recession,” he said.

He continued: “People aren’t going to buy anything. I gotta tell my members not to buy anything. They gotta pay rent and food for their kids.”

Ali Abbas Ahmadi/BBC

Ali Abbas Ahmadi/BBCWhat makes the tariffs such a hard pill to swallow for auto workers the BBC spoke to is that this situation has been brought about by the US, Canada’s closest economic and security ally.

“It seems like a stab in the back,” said Austin Welzel, 27, an assembly line worker at Stellantis. “It’s almost like our neighbors, our friends – they don’t want to work with us.”

Christina Grossi, who has worked at Ford for 25 years, said the prospect of losing her job, and what it will mean to her family, is “terrifying”.

But Ms Grossi also fears losing the meaning she gets from her work.

“You’ve been doing this job for so long and you really take pride in it, you’re proud of what you’re putting out to the public,” she said. “And now someone’s taking away the opportunity to do that.”

Laura Dawson, the executive director of Future Borders Coalition, said the tariffs could cause major upheavals throughout the sector due to its deep integration, with ripple effects felt across the continent if exports from Canada stop for more than a week.

She said the US tariffs structure is extremely complicated.

Cars crossing the border will need every component to be assessed for “qualifying content” – where it originates, the cost of labour to produce it, and – if it contains steel or aluminium – where that metal came from.

“Every part of an automobile is literally under a microscope for where it was produced and how,” she said.

The US tariffs have been a major factor in Canada’s general election, which is on 28 April, with Canada’s political parties rolling out suites of plans on the campaign trail to help the auto sector.

Liberal leader Mark Carney, the current prime minister, has pledged to create a C$2bn ($1.4bn; £1.1bn) fund to boost competitiveness and protect manufacturing jobs, alongside plans to build an “all-in-Canada” auto component parts network.

In his role as prime minister, he imposed last week a reported C$35bn in counter auto tariffs, in addition to previously announced reciprocal measures on the US.

Carney’s main rival, Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre, has vowed to remove sales tax on Canadian vehicles, and to create a fund for companies affected by the tariffs to help keep their employees.

Jagmeet Singh, whose left-wing New Democratic Party is fighting for a competitive seat in Windsor, has pledged to use every dollar from counter tariffs to help workers, and to stop manufacturers from moving equipment to the US.

Ali Abbas Ahmadi/BBC

Ali Abbas Ahmadi/BBCStill, Windsor’s economy is dependent on automakers, and heavily relies on trade with the United States. If it falters, everything – from restaurants to charities – will feel the effects.

The Penalty Box is a sports bar just down the road from the Stellantis plant, and popular with the workers there.

“We’re one of the busiest restaurants. I don’t want to say it, but if you ask around about the Penalty Box, they’ll tell you,” its 70-year-old owner, Van Niforos, said. “We do close to 1,000 meals a day.”

With a white apron and a wide smile, he relates its 33-year history. But his demeanour darkens when asked about threats the auto sector faces.

“It’s a devastating situation. I don’t want to think about it,” he said.

“We employ 60 people and we’re open six days a week. [If something happens to the Stellantis plant], will we be able to keep 60 people working? Absolutely no.”

Chad Lawton, sitting in his office at the local union, takes a deep breath as he contemplates how precarious his life feels.

He doesn’t think Carney’s counter tariffs help the current situation, arguing they “just makes a really bad situation a little bit worse”.

He hopes there is room for trade negotiation, but said he will be the first to say that Canada “cannot just concede and roll over”.

“I’ve worked for a Ford Motor Company for almost 31 years, and I have never seen anything close to this,” he said.

“That includes Covid, because at least with Covid, we knew what we were dealing with. And there was some certainty there.”

“This is all over the map.”